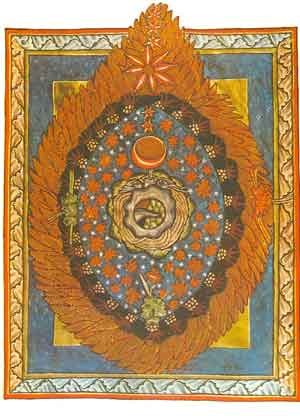

Hildegard von Bingen is a fascinating and singular historical figure, hailing from a now distant period of Western culture which isn’t commonly known for its creative output. Particularly as a woman in 12th century Europe, who arguably challenged the status quo for her gender with some regularity, she stands out all the more. In my all too brief study of the intriguing personality embodied in this remarkable abbess, ecstatic visionary, musical composer, and visual artist, I learned many interesting things. It wasn’t easy to rule out so many possibilities. But I did eventually – assisted by a beautifully simple illumination of hers – known to us as The Egg of the Universe.

There are SO MANY things to say about this. The first thing, and the reason that my eye was arrested by this image is that it bears undeniable resemblance to the genitalia of a human female. Comparison to an anatomical diagram further confirmed this for me. Yet, this image has come to be known as an egg – and in fact was identified as such by Hildegard herself. “By this supreme instrument in the figure of an egg, and which is the universe,” she wrote, “invisible and eternal things are manifested.” [Fox, 1985,2002] I can’t help but wonder though. The physiological similarities are too many to pass for mere coincidence, in my humble opinion. I probably need not instruct the reader on this but, to explain and demonstrate my recently more nuanced education in this regard: In the center of this mandala, we have the Earth, per the Ptolemaic model. Moving upward: a crescent moon, followed by the inner planets Venus and Mercury, then the Sun and three of the then known outer planets – Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. In human anatomy, these correspond strikingly well with the Vaginal orifice, Urethra, and Clitoris, respectively. Moving outward from the Earth are the stars in all directions, then a ring punctuated by hail and lightning. Encompassing all, as Hildegard described, is a ring of fiery firmament. “On the outer part along the circle was a bright flame, and in that fire was a globe of reddish fire so great that the entire egg was being lit up by it.” [Fox, 1985,2002] (It is important to note that Hildegard was recounting no mere invention of imagination, but the memory of a vision so intense that it was at times difficult for her to look upon). The starry ether, stormy atmosphere, and fiery heavens are an easy visual match for those genitalic parts of the female body known as the Vestibule, Labia minora, and Labia majora. While it is no stretch to view this image as an egg, it cannot have evaded the intellect of Hildegard, nor of all her contemporaries, that she had produced a rather detailed and accurate anatomical diagram of a woman’s external genitalia. In my admittedly inadequate reading however, there is very little attention paid to this thinly disguised celebration of the female body – and the fact that it appeared in a time and place in which it might have been viewed with considerable hostility . However, a cursory survey of results from the Google search, “hildegard’s egg of the unviverse is a vagina” was enough to demonstrate that I am far from alone in this observation. It is fascinating to consider what Hildegard may have seen, felt, thought, and tried to communicate about the physical bodies of people, and especially about the bodies of women.

Rather than to explicitly emphasize the sexuality or femininity of Hildegard’s egg, she and her modern commentator Matthew Fox prefer to make an analogy for the egg as a model of the universe. Fox makes several observations, based upon Hildegard’s own explanation. Among them, that the egg is a symbol of universal interconnection, that the universe, viewed in this way, is incipient, organic, creative, and evolving – and that humans have been endowed with the gift of the ability and invitation to be co-creators with God.

On the Egg as a Unity:

Fox quotes from Hildegard’s Uhlein, “O Holy Spirit, you are the mighty way in which every thing that is in the heavens, on the earth, and under the earth, is penetrated with connectedness, penetrated with relatedness.” [Fox, 1985,2002] He believes that Hildegard intended to describe a ubiquitous and complete connection throughout the universe – as he wrote, “You cannot separate god and cosmos, Christ and cosmos, humans and cosmos, in Hildegard’s thought.” [Fox, 1985,2002] Fox informs us that Hildegard was an avid and dedicated scholar of the contemporary science, citing her assertion, “all science comes from God.”

On the Living, Breathing, and Creative universe

Fox writes on, “An egg is the beginning of something wonderful, a new being, a new creation …… By picturing the cosmos as an egg, Hildegard is distancing herself from Plato and all those who through the ages have envisioned the universe as essentially static.” [Fox, 1985,2002] I appreciate this characterization. After all, modern astro-physical cosmology shows that we are the literal progeny of the cosmos, that we have inherited our very bodies and the earth upon which we stand from the exploded forms of our ancestors, the deceased stars. The cosmos are not remote, they are inside us. They are us, and we are them – and from them all things have come. From them issues the immeasurably diverse birthing of existence, from the infinitesimal to the infinite.

Co-creators with God

“God gave to humankind the talent to create with all the world,” Hildegard observed.” [Fox, 1985,2002] If people are made in the image of God, perhaps the best illustration of this can be found in the inexhaustible propensity for human invention. We are driven to create. To find new forms and to discover new beauty – indeed to conjure ideas, images, structures, and systems which have yet to be imagined. These endeavors have consumed the collective attention of humanity from time immemorial – and we show no signs of slowing. While stumbling often, in the upward climb toward collective self-actualization, our apish species has produced creations of breathtaking and awesome sublimity.

During my brief attempt to peer into the mind of such an extraordinary human in the writing and art of Hildegard von Bingen, I learned other things of great interest to students of many fields. I learned that despite her many wonderful works, they laid in near complete obscurity until a late 20th century wave of scholarly feminism unearthed her buried treasures, so to speak. I perused the writings of those who argued over what Hildegard had to do, if anything with modern feminism [Collingridge, Lorna. Please Don’t Talk about Hildegard and Feminism in the Same Breath!ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1257&context=mff]. I scanned a neuroscientific article which attempted to explain the unusual physiological conditions of Hildegard which may have produced a series of ecstatic visions, of which the Egg of the Universe is but one of many. And I found that she preceded later theological luminaries such as Julian of Norwich. [Hudson, Jennifer A. “‘God Our Mother’: The Feminine Cosmology of Julian of Norwich and Hildegard of Bingen.” Medieval Forum, 25 Sept. 2002, http://www.sfsu.edu/~medieval/Volume 1/Hudson.html.]. I can see that I have barely begun to scratch the surface of the significance of the life and work of Hildegard von Bingen.

Works Cited:

Fox, Matthew, and Hildegard. Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen. Bear & Co., 2003.

[Collingridge, Lorna. Please Don’t Talk about Hildegard and Feminism in the Same Breath!ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1257&context=mff]

[Hudson, Jennifer A. “‘God Our Mother’: The Feminine Cosmology of Julian of Norwich and Hildegard of Bingen.” Medieval Forum, 25 Sept. 2002, http://www.sfsu.edu/~medieval/Volume 1/Hudson.html.]

Notes:

At least sometimes, Hildegard used female pronouns to refer to God. Fox quotes: “…all the things (sun, moon, stars, wind, rain) are obedient to their Creator according to her command.” (italics and parenthetical content added) Again, “O humans, God is just, there has arranged with a just arrangement all the things which she made on heaven and on earth.”

These references to divinity in feminine terms dovetail with thoughts I had when I first noticed the anatomical resemblance of the Egg of the Universe. How did her contemporaries respond, if they were aware? Julian of Norwich wrote of Christ as a “moder”, a mother, in the late 14th century. What happened to the Christian notion of the feminine or perhaps more accurately, gender balanced divinity? Why has it receded from all but the most remote corners of Western religious culture, and culture at large? What precipitated the shift toward a much more rigid and paternal view of God in the West, and what has our society lost as a result?

Copied from the work of others, but not worked into my text:

Her conceptualization of the universe in Scivias falls within the Ptolemaic tradition, but Hildegard modifies this tradition through her motif of the world as the fruitful center of the universe, an egg (Gossmann 35). It refutes Plato’s conceptualization of the male as the “begetter” and female as the passive “Mother Receptacle” on the cosmic level and instead places Mother Earth as center of the universe and powerful creatrix. She is not passive, but active in her generative energy. [“God our Mother”: The Feminine Cosmology of Julian of Norwich and Hildegard of Bingen Jennifer A. Hudson]

Moreover, Hildegard uses the feminine form in Latin, sapienta Dei, whenever she discusses Christ, which is similar to Julian’s use of “God our Mother.” Hence it is not so much that God exists as a sexless entity for Hildegard, but rather as a balanced higher power that possesses a blend of masculine and feminine characteristics.